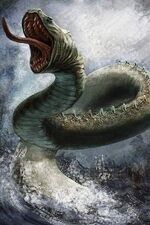

. He was the source of devastating storm winds which issued forth from that dark nether realm.

Later poets described him as a volcanic-daimon,

trapped beneath the body of Mount Aitna in Sicily. In this guise he was

closely identified with the Gigante

.

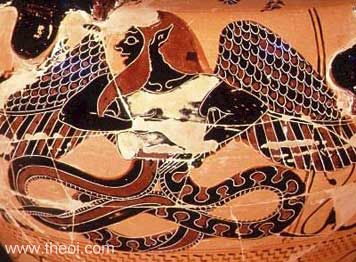

Typhoeus was so huge that his head was said to brush

the stars. He appeared man-shaped down to the thighs, with two coiled

vipers in place of legs. Attached to his hands in place of fingers were a

hundred serpent heads, fifty per hand. He was winged, with dirty matted

hair and beard, pointed ears, and eyes flashing fire. According to some

he had two hundred hands each with fifty serpents for fingers and a

hundred heads, one in human form with the rest being heads of bulls,

boars, serpents, lions and leopards. As a volcano-daimon, Typhoeus

hurled red-hot rocks at the sky and storms of fire boiled from his

mouth.

, but Thor will only walk nine paces before dying himself, of the serpent's poisonous venom.

Loki was punished by the gods as a result of his betrayal; he was

placed in the deepest depths of Hel, with Jormungandr dripping poison in

his face. He was, however, allowed a respite. His wife stood next to

him, and caught the drops of poison in a bowl before they could strike

his face. Periodically, however, she would have to empty the bowl over

his face, and he would writhe in agony, creating earthquakes. So was

Jormungandr caught, stuck to a rock in the deepest pit in Hel, torturing

Loki forever.

In one adventure, Thor encounters Jörmungandr in the form of a colossal cat, disguised by the giant king

's

illusionary magic. As one of the challenges set by Útgarða-Loki, Thor

must lift the cat, and though he is unable to lift such a monstrous

creature as the Midgard snake, he manages to lift it far enough that it

lets go of the ground with one of its four feet. When Útgarða-Loki later

reveals he deceived him it seemed like an incredible heroic feat.

Long ago, Thor decided to catch Jormungandr, and kill him. This would

prove difficult as the Midgard Serpent reached almost around the whole

world and lay in the deepest depth of the ocean. But Thor did not

despair. He took his trusty hammer and went to the giant Hymir, who went

fishing. Hymir was friendly, and let Thor sleep in his house, and said

he could go fishing with him the next morning. The next morning, Thor,

who had to provide his own bait, went to Hymir's cattle pen, and took

the largest ox's head with him to use as bait. He got into the boat with

Hymir, and started rowing. Soon they had reached where Hymir usually

went fishing, and wanted to stop, but Thor rowed on. "This is enough!'

the giant soon said. "We may even chance upon the Midgard Serpent here,

and we will go no further.' Thor threw out his unbreakable line, and the

ox's head sunk to the bottom, right in front of the Serpent, who

greedily devoured it whole. Immediately it pulled so hard on the line

that Thor broke his knuckles upon the edge of the boat, and got very

angry. He pulled up the Mudgard serpent, thrashing and well, from the

bottom of the sea. He had almost reached the surface, and Thor was

readying his hammer to strike it, when the scared Hymir cut the line.

The serpent sank back to the bottom of the sea, and Thor threw his

hammer at it. Then he punched the giant so hard he fell overboard, and

waded back through the sea to the far-away shore.

Ben Vair Dragon:

In Argylllshire, Scotland - The hero of this story was a sea captain,

Charles the Skipper. He came up with a trap to rid the area of a dragon

that was the bane of all. He anchored his ship a little way offshore,

and built a bridge from the vessel to the beach.

The bridge was made of barrels lashed together and studded with metal

spikes. The sea captain began to roast some meat on his ship. The smell

wafted to the dragon’s lair and it came swooping down to the beach. As

it began to crawl across the bridge of barrels, the spikes pierced its

hide and one struck the dragon’s vulnerable spot. The massive beast

expired on the bridge long before it got to the ship.

INDIAN NAGAS AND DRACONIC PROTOTYPES

AT A very early period northern India acquired a mixed population

composed of Conquerors and more peaceful immigrants from the west and

north, which became amalgamated with whatever remained in the previous

inhabitants; and an antique form of Sanscrit spoken by the invaders

became the general language. They appear, as far back as they can be

traced, to have been an agricultural and cattle-breeding people, using

horses, settled mainly in towns and villages, and considerably advanced

towards civilization. Their religious ideas, at least within the

millennium next preceding the beginning of the Christian era, as we

learn from the Vedas, were expressed in a mythology of nature-gods

related to the sun and sky and, especially to the weather as affecting

grass and crops, with which was mixed a very ancient and fetishistic

serpent-worship. In short these ancestral Hindoos much resembled in

ideas the people of Elam and Chaldea with whom they were already in

communication, but far exceeded them in their reverence of

serpents--naturally, perhaps, as these are more numerous and dangerous

in India than in Mesopotamia.

Their particular object in serpent-veneration was the deadly cobra,

called naga; and every one of these hooded reptiles was regarded as the

living incarnation or representative of a great and fearful company of

mythological nagas. These were demi-gods in various serpentine forms,

uncertain of temper and fearful in possibilities of harm, whose 'kings'

lived in luxury in magnificent palaces in the depths of the sea or at

the bottom of inland lakes. They were also said to inhabit an underworld

(Patala Land), and were believed to control the clouds, produce

thunderstorms, guard treasures, and do weird and marvellous things in

general. Many feats were attributed to them which could be performed

only by beings having human powers and faculties, whence they were said

to assume human form from time to time; and stories are told in the

writings of 'naga-people' appearing mysteriously and then escaping to

the depths of the ocean--probably developed from incidents in which wild

strangers had raided the coast and when discovered had fled over the

horizon in their boats. The ruder tribes, which were most addicted to

cobra-worship, and were despised by the Brahmanic class, were known as

Naga men or simply Nagas. This cult persists in remote districts to this

day, and is especially vigorous in the rough country of northern Burma

and Siam, where temples of snake-worship are yet maintained. Doubtless

it formerly prevailed beyond India all over the Malay Peninsula and

among the unknown aborigines of China.

It must be remembered in connection with these facts that the

semi-civilized inhabitants of the Northwest were largely a maritime

people. Living along the great Indus River they early took to the sea

and became daring navigators, voyaging far eastward on both plundering

and trading expeditions. The civilization of both Burma and Indochina,

according to Oldham's investigations, is shown by history as well as

legend to be owing to invaders from India, who introduced there not only

ideas of a settled life and trade, but taught the notions of

naga-worship, and later Buddhistic doctrines and practices throughout

southern China, Java, Sumatra and Celebes. Buddha himself refers to such

voyages, in which no doubt religious missionaries sometimes

participated.

Mingled with this was direct reaching from Babylon and Egypt, as has

already been mentioned. "Within twenty years of the introduction of the

Phoenician navy into the Persian Gulf by Sennacherib traders from the

Red Sea arrived in the gulf of Kiao-Chau, and soon established colonies

there." This was in the middle of the sixth century B.C. "They came on

ships bearing bird or animal heads and two big eyes on the bow, and two

large steering-oars at the stern--distinctly Egyptian methods of

ship-building."

Into the Vedic civilization of northern India, was introduced, about

the seventh century B.C., the more spiritual and unselfish cult of

Buddhism. Its most difficult problem was the overcoming of

cobra-worship, and as this proved impossible, the Buddhists were

compelled to be content with trying to improve the worst features of

ophiolatry among the Naga tribes; but this conciliatory attitude seems

to have led to a weakening and corruption of the gospel preached by

Buddha and his first apostles. Legends, though conflicting, indicate

this. It is related, for example, that a naga king foretold the

attainment of Gautama to Buddhahood; and the cobra-king who lived in

Lake Mucilinda sheltered Lord Buddha for seven days from wind and rain

by his coils and spreading hoods, as is represented in many antique

pictures and sculptures. At any rate a schism developed over this

matter, resulting in the southern Buddhists teaching less strict

doctrine with reference to the old beliefs, which became known as the

Manhayana school.

The nagas' ability to raise clouds and thunder when out of temper was

cleverly absorbed by this school into the highly beneficent power of

giving rain to thirsty earth, and so these dreadful beings became by the

influence of Buddha's 'Law' blessers of men. "In this garb," as Dr.

Visser' points out, they were readily identified with the Chinese

dragons, which were also beneficent rain-gods of water"; and it was this

modified, semi-Hindoo, Manhayana conception of Buddhism, with its

tolerance of serpent-divinity, which was carried by wandering

missionaries and traders during the later Han period into China and

eastward.

Visser ascertained, in his profound examination of this serpent-cult,

that in later Indian, that is Greco-Buddhist, art, the nagas appear as

real dragons, although with the upper part of the body human. "So we see

them on a relief from Gandahara, worshipping the Buddha's alms-bowl in

the shape of big water-dragons, scaled and winged, with two horse-legs,

the upper part of the body human." They may be found represented even as

men or women with snakes coming out of their necks and rising over

their heads, which recalls the prime fiends of Persian legend, and also

the prehistoric pictures of the more or less mythical Chinese sage Fu

Hsi.

The four classes into which the Indian Manhayanists divided their nagas were (quoting Visser):

Heavenly Nagas--who uphold and guard the heavenly palace.

Divine Nagas--who cause clouds to rise and rain to fall.

Earthly Nagas--who clear out and drain off rivers, opening outlets.

Hidden Nagas--guardians of treasures.

This corresponds closely with Professor Cyrus Adler's list (Report U.

S. National Museum, 1888), of the four kinds of Chinese dragons: "The

early cosmogonists enlarged on the imaginary data of previous writers

and averred that there were distinct kinds of dragons proper--the

t'ien-lung or celestial dragon, which guards the mansions of the gods

and supports them so that they do not fall; the shen-lung or spiritual

dragon, which causes the winds to blow and produces rain for the benefit

of mankind; the ti-lung or dragon of the earth, which marks out the

courses of rivers and streams; and the fu-ts'ang-lung or dragon of

hidden treasures, which watches over the wealth concealed from mortals.

Modern superstition has further originated the idea of four dragon

kings, each bearing rule over one of the four seas which form the

borders of the habitable earth."

In a Tibetan picture referred to by Visser nagas are depicted in

three forms: Common snakes guarding jewels; human beings with four

snakes in their necks; and winged sea-dragons, the upper part of the

body human, but with a horned, ox-like head, the lower part of the body

that of a coiling dragon. This shows how a queer mixture of Chaldean,

Persian and Hindoostanee elements reached Tibet by very ancient caravan

roads north of the Himalayan ranges; and it throws light on one possible

origin of the four-legged figure adopted by the Chinese, especially in

the northern marches of the empire where the inhabitants were open to

Bactrian, Scythian, and other western influences.

That composite animal-form of the rain-god of the Euphrates people,

the horned sea-goat of Marduk (immortalized as the Capricornus of our

Zodiac), was also the vehicle of Varuna in India, whose relationship to

Indra was in some respects analogous to that of Ea to Marduk in

Babylonia. In his account of Sanchi and its ruins General Maisey, as

quoted by Smith, states that: "As to the fish-incarnation of Vishnu and

Sakya Buddha, and as to the makara, dragon or fish-lion, another form of

which was the naga of the waters, the use of the symbol by both

Brahmans and Buddhists, and their common use of the sacred barge, are

proofs of the connection between both forms of religion and the far

older myths of Egypt and Assyria." Havell is of the opinion that the

crocodile-dragon which appears in the figure of Siva dancing in the

great temple of Tanjore, may have been older than the eleventh century

when the temple was built. "In the earlier Indian rendering of this

sun-symbolism, as seen in the Buddhist 'horse-shoe' arches," says

Havell, "the crocodile-dragon, the demon of darkness, who swallows the

sun at night and releases it in the morning, is not combined with these

sun-windows until after the development of the Manhayana school."

Sun-worship, serpent-worship, phallicism, and dragons are inextricably interwoven in Oriental mythology.

It is in the Indian makara, I think, that we have the 'link' between

the Western conception and that of the Chinese as to the shape of this

fabulous water-spirit. Yet, all the makaras of Vedic myth are simply a

crocodile in simple form, or else are variants of Marduk's sea-goat with

two front feet only, varied according to the head and body into

antelopes (blackbuck), cats, elephants, etc., all carrying fish-tails.

The Chinese dragon, on the other hand, has nothing of the fish about it,

but is wholly serpent, except its horned and fantastic head and the

fact that it invariably possessed (crocodile-like) four legs and feet

which are quite as like those of a bird as like those of a lion. There

is evidently some significance in the bird-like feet. Can they be a

relic of the introduction ages ago of the Babylonian or Elamite figure

of the rain-god, composed by joining the symbols of Hathor-Sekhet and

Horus? That is to say, do they possibly represent the long-forgotten

falcon of the bright son of Osiris?

"In Chinese Buddhism," Dr. Anderson informs us in his celebrated

Catalogue, "the dragon plays an important part either as a fierce

auxiliary to the Law or as a malevolent creature to be converted or

quelled. Its usual character, however, is that of a guardian of the

faith under the direction of Buddha, Bodhisattvas, or Arhats. As a

dragon king it officiates at the baptism of the Sakyamuni, or bewails

his entrance into Nirvana; as an attribute of saintly or divine

personages it appears at the feet of the Arhat Panthaka, emerging from

the sea to salute the goddess Kuanyin, or as an attendant upon or

alternative form of Sarasvati, the Japanese Benten; as an enemy of

mankind it meets its Perseus and Saint George in the Chinese monarch Kao

Tsu (of the Han dynasty) and the Shinto god Susano'no Mikoto. When this

religion made its way into China, where the hooded snake was unknown,

the emblems shown in the Indian pictures and graven images lost their

force of suggestion, and hence became replaced by a mythical but more

familiar emblem of power."

It was mainly--but not altogether, as we shall see--from Indian

sources that the now familiar four-footed dragon of China became

conventialized through its applications in the several arts of

decoration and devotion; and it seems a fair inference that the

aggressive Buddhist influence of the early centuries of that sect led

Chinese artists to change the smooth, well-proportioned ch'ih-lung of

their forefathers, chin-bearded like the ancient sages, into a sort of

jungle python with the horrifying head and face characteristic of the

countenances of antique Buddhistic images of their demons. To understand

how inhumanly terrible these caricatures of malignant beings in the

guise of humanity may be, one need only glance at drawings of the temple

images exhumed by Sir Aurel Stern from the sand-buried Indo-Chinese

cities of Turkestan, which flourished about the time of which I am

speaking.

Buddhist artists, at first probably aliens, would be likely to depict

the dragon head and face in their attempts to portray the chief

'demon', as they mistakenly regarded the friendly Chinese divinity,

after the same horrifying fashion. Then, to impress the people of the

North, who saw few dangerous snakes, but who did know and fear tigers

and leopards, the artists equipped their frightful-headed serpent with

catlike legs, bird's feet, such tufts of hair as decorate and would

suggest a lion, and a novel ridge of iguana-like spines along its

backbone.

The fully realized dragon, then, as we see it in bronzes or sprawled

across a silken screen, is an invention of decorative artists striving,

during the last 2000 years, to embody a traditional but essentially

foreign idea.

Mayan mythology emerged from the traditions and religion of a civilization as old as 3,000 years from a vast region called Mesoamerica: territories that are now the Mexican states of Campeche, Chiapas, Quintana Roo, Tabasco, and Yucatan, in addition to some parts of Central America.

Even though many of the texts written by the Mayans were burned on the

arrival of the Spanish, some legends have survived and continue to be

told today.

Mayan mythology emerged from the traditions and religion of a civilization as old as 3,000 years from a vast region called Mesoamerica: territories that are now the Mexican states of Campeche, Chiapas, Quintana Roo, Tabasco, and Yucatan, in addition to some parts of Central America.

Even though many of the texts written by the Mayans were burned on the

arrival of the Spanish, some legends have survived and continue to be

told today. The aluxes are tiny beings, created out of clay that were hidden and in that way they were able to protect its owner. The aluxes

(pronounced ah-lu-shes), had a strong tie to their creator. Once they

were created, they were offered prayer and offerings to make them come

to life.

The aluxes are tiny beings, created out of clay that were hidden and in that way they were able to protect its owner. The aluxes

(pronounced ah-lu-shes), had a strong tie to their creator. Once they

were created, they were offered prayer and offerings to make them come

to life. Pronounced

eesh-ta-bai, this legend tells the story of two beautiful sisters. One

of them was known as the sinner and the other as the good one. The first

one was not wanted because she gave herself to love, but in reality was

loved by the sick and the weak ones. The second one was appreciated by

the town, but in the interior she was rigid and incapable of loving

those around her.

Pronounced

eesh-ta-bai, this legend tells the story of two beautiful sisters. One

of them was known as the sinner and the other as the good one. The first

one was not wanted because she gave herself to love, but in reality was

loved by the sick and the weak ones. The second one was appreciated by

the town, but in the interior she was rigid and incapable of loving

those around her. Sac-Nicte

means white flower. She was born in Mayapan: the powerful alliance that

lived in peace—Mayab, Uxmal, and Chichen Itza. Canek means black

serpent, a brave prince with a kind heart. When he turned 21 years of

age, he was chosen as king of Chichen Itza. That same day he met

princess Sac-Nacte. She was 15 years of age. Both quickly fell in love;

however Sac-Nicte was destined to be married with young Ulil, prince of

Uxmal.

Sac-Nicte

means white flower. She was born in Mayapan: the powerful alliance that

lived in peace—Mayab, Uxmal, and Chichen Itza. Canek means black

serpent, a brave prince with a kind heart. When he turned 21 years of

age, he was chosen as king of Chichen Itza. That same day he met

princess Sac-Nacte. She was 15 years of age. Both quickly fell in love;

however Sac-Nicte was destined to be married with young Ulil, prince of

Uxmal. Uxmal

is pronounces ush-mal. The legend says that a long time ago in the

ancient Mayan city, there lived an ancient woman that worked as an

oracle in the city. The woman was unable to conceive children and

therefore asked the god Chic Chan to bring her the shell of a large

turtle. A few months later, a tiny green dwarf with red hair was born.

Uxmal

is pronounces ush-mal. The legend says that a long time ago in the

ancient Mayan city, there lived an ancient woman that worked as an

oracle in the city. The woman was unable to conceive children and

therefore asked the god Chic Chan to bring her the shell of a large

turtle. A few months later, a tiny green dwarf with red hair was born.